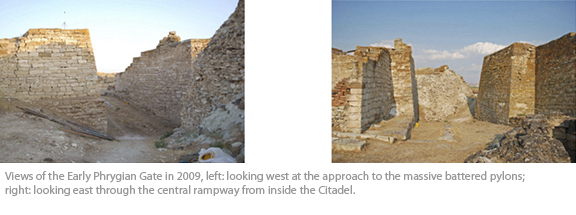

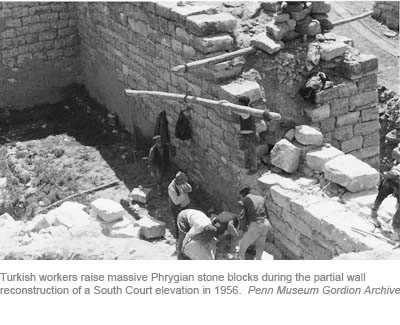

First excavated in the 1950s by a team of archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Early Phrygian Gate is the largest extant gate to survive from the Iron Age in the Middle East. However, its dry laid construction (built without the use of mortar) leaves it vulnerable to the region’s high seismic activity. Constructed around 900 BCE, the Early Phrygian Gate served only briefly as the main entryway to the citadel. Successive periods of occupation within the citadel mound resulted in a new gate which utilized the earlier structure as a foundation for new construction. The changing load patterns produced by the new superimposed structures caused visible damage—most notably masonry cracking and displacement. Although cracking occurred historically from the additional loads of the later city walls, displacement continues to be an active condition. From 2006-2010, the Architectural Conservation Laboratory and Engineer Dr. Ahmet Turer from METU have conducted a detailed program to document, monitor and assess the gate’s overall structural stability and determine the condition of its limestone walls. |