| In

1844 William Strickland warned Collector Judge Blythe that "the whole

of the interior as well as the exterior required a thorough cleansing

and repair, particularly in the items of carpentry, masonry, painting

& glazing... The marble columns and architraves of the principle

business room required scrubbing with pumice stone, to remove the dust

of the years..."

|

| | Stone

deterioration on the Bank triggered stone repair in the early 1920’s

when some loose stone was removed from the columns. The stone

deterioration was considered severe enough for the federal government

to request from the Obelisk Waterproofing Company of New York and the

Avron Company of Philadelphia estimates for waterproofing the entire

exterior of the structure. The Obelisk Company gained notoriety for

applying hot paraffin wax on Cleopatra's Needle in 1885 hence the

company’s name. Paraffin has a low melting point, which during hot days

causes dust and particulates to adhere to the surface. Photographs from

1940 show the building covered with black deposits, which might be

explained by the hot wax treatment that the Obelisk Company might have applied.

In

1923, Edward Crane, consulting architect, reported that several pieces

of marble had fallen off, especially from the columns. He agreed that

the building should be cleaned, repointed, and waterproofed. The use of

a waterproofing compound “could do no harm and might prove a real

preservative." For cleaning, he recommended that soap and water should

be used with "a good stiff brush.”

| | In

May 1942 the exterior marble was cleaned and waterproofed, but no

records were found describing the cleansers, tools, or methods used.

Photographs show that the columns and the ashlar of the south facade

were cleaned from the bottom up, with the northern elevation being done

at about the same time in a similar pattern. The east and west facades

were cleaned in sections starting at the southern and northern ends and

working towards the middle.

From

1964-1973, the bank underwent a series of alterations and in 1975, was

reopened as a Portrait Gallery. In 1994, in response to observed stone

failure, a preliminary

assessment of the exterior masonry and characterization and analysis of

the stone was initiated by the National Park Service (INHP) and the

Architectural Conservation Laboratory of the Graduate Program in

Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. This led to

temporary protection and emergency stabilization of critical areas of

the entablature for public safety and laboratory testing of potential

consolidation methods. Historically there has been periodic dimensional

loss of the marble through spalling on the columns and along the

entablature. Additionally, in unsheltered areas of the ashlar walls,

many stones display a deep pattern of loss through contour scaling of

the stone faces.

Only

small-scale repairs were conducted in the 1980's and 1990’s. From 1983

to the present, several fragments of marble had

fallen off and were adhered back in place with epoxies and other

methods. To prepare the areas the damaged stone was cut away to insure

a good key.

In

1999 following these initial studies, a multi-phased conservation plan

was developed by the ACL and the National park Service and initiated

with the preparation of a detailed computer-based survey of the

exterior masonry conditions and the compilation of a history of past

repairs and treatments to the building. |

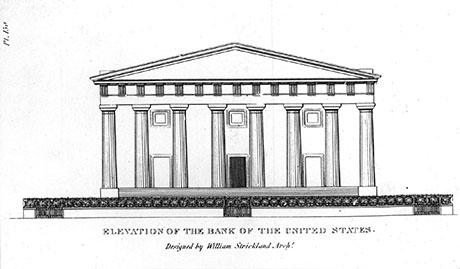

| |  | | Elevation Drawing, William Strickland, 1821 |

|

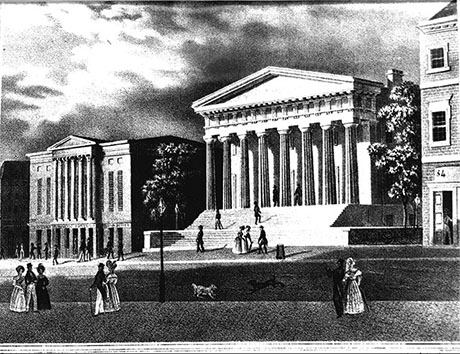

| | United States Bank, J. C. Wild Lithograph, 1838 |

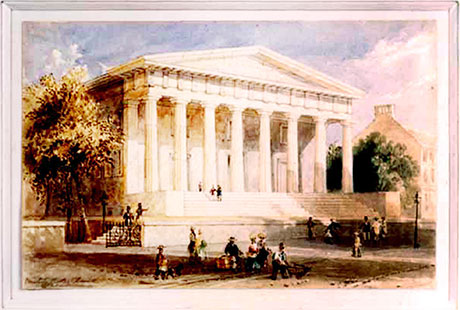

|  | | United States Bank, Bartlett Watercolor, 1836 |

|  | | South Elevation, National Park Service, 1942 |

|

|

|

|